She was usually represented as a cow goddess. Her manifestations and associated activities were many and varied, and her other aspects such as love and hate, or creation and destruction, characterized her from the earliest stages of her worship.

Hathor's origins and worship

Because she was a prehistoric goddess, it is difficult to discern the origins of her nature and worship, but her presence is evident from prehistoric times continuously into the period of Roman domination.Her aspects included animals, plants, sky, sun, trees and minerals, and she ruled the realms of love, sex and fertility, and she also had a vengeful side capable of destroying humanity.

The name Hathor in Egyptian, ḥwt-ḥr, means ‘House of Horus’ and is written in Hieroglyphics with a rectangular sign of a building, with the symbol of the falcon Horus inside.

|

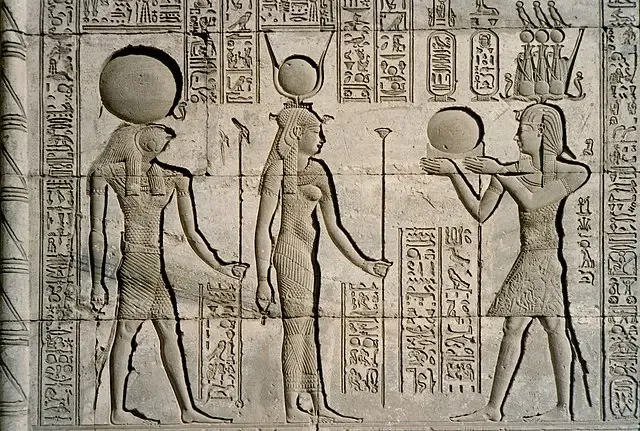

| Relief at Dendera Temple showing Traianus (right), Horus (left), and Hathor (center), Dendera, Egypt. Photo: Bernard Gagnon, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license (CC BY-SA 3.0). Source: Wikimedia Commons. |

| Category | Hathor — Key Facts |

|---|---|

| Primary Roles | Goddess of love, beauty, music, fertility, joy, and protection of women; also a funerary aspect as “Lady of the West”. |

| Epithets/Titles | “Mistress of Dendera”, “Foremost of Heaven”, “Lady of the West”, “Eye of Ra”. |

| Symbols & Ritual Objects | Cow horns with solar disk; menat necklace; sistrum (ritual rattle); mirror. |

| Animal/Iconography | As a cow; or a woman with cow’s ears/horns and solar disk; sometimes lioness aspect in Eye-of-Ra traditions. |

| Main Cult Centers | Dendera (primary), with worship attested widely across Egypt (incl. Thebes). |

| Key Myths & Links | Often identified as the Eye of Ra; linked with Horus/Ra (royal motherhood); associations with Isis, Sekhmet, and music/joy. |

| Festivals | “Festival of Drunkenness” (Tekh): ritual celebration of joy/renewal connected to the Eye-of-Ra cycle. |

| Royal Associations | Symbolic mother of the pharaoh; queens adopt her headdress; patron of music/dance in court and temple rites. |

Representations of Hathor

In later periods, the headdress may include two long feathers standing between the horns; or she may wear an eagle's hat.

Hathor often wore a minat, a necklace made of many strands of beads balanced by a heavy pendant at the back.

Hathor is also often depicted as a cow, usually holding the sun disc between her horns and wearing a minat necklace.

|

| Stela of a Priest of Amun, ca. 1426–1390 B.C.E., limestone, Brooklyn Museum (Accession #16.92). Photo by 'one_click_beyond' for Wikipedia Loves Art, licensed under CC BY 2.5. |

Another form of Hathor is a female face seen from the front, with cow ears and a curly wig.

This face appears on certain types of votive objects and could form the capitals of columns in temples dedicated to the goddess.

|

| Hathor, goddess of music, at Louvre-Lens Museum, Lens, France. Photo taken on 5 January 2018 by © Pierre André, licensed as own work. |

The roots of Hathor's worship can be found in pre-dynastic cow worship, where wild cows were venerated as the embodiment of nature and fertility.

Even in early depictions of her, Hathor's multifacetedness was evident. For example, the rim of a stone jar from Hierakonpolis, dating from the First Dynasty, is decorated with the face of a cow goddess with stars on the tips of her horns and ears, signaling her role (or Bat's role) as a sky goddess as in the Narmer stela.

This role may be related to her relationship with Horus, as he was a god of the sun and sky, Hathor, as his ‘home’, resided in the sky as well.

Hathor in funerary texts

Evidence for this belief appears in funerary texts: as early as the pyramid texts, the pharaoh is said to ascend to Hathor in the sky, and this is similarly mentioned in sarcophagus texts.Hathor was a tree goddess and was of great importance to the deceased, providing shade and drinking from her branches.

Hathor's appearance as a tree goddess originated in the Nile Delta, and in this role she had a close relationship with Ptah, the god of creation from Memphis.

In the New Kingdom, there is a legend that Ptah attended a procession to visit Hathor, who was referred to as Ptah's daughter. Hathor was also a goddess associated with love, sex and fertility.

Hathor as the goddess of love and fertility

In another ivory inscription from the First Dynasty, Hathor is shown surrounded by signs of Min, a god known for fertility, indicating their affiliation.The Greeks likened her to Aphrodite, their goddess of love and beauty. There are many hymns glorifying her and praising the joy and love for which she was responsible, and she is often addressed in these hymns as “Golden,” a name of unknown origin.

Throughout the history of her worship, Hathor received as offerings a variety of fertility figurines, as well as the male phallus, and was considered a source of assistance in conception and childbirth.

One of her titles was “Lady of the Vulva,” and she appears in medical texts as well as in prayers related to pregnancy and childbirth.

|

| Ptolemaic plaque from Dendera depicting a woman giving birth, assisted by two cow-headed goddesses symbolizing Hathor. Photo by A. Parrot, licensed under CC0. |

Hathor as a funerary goddess

Hathor was an important funerary goddess. In Thebes, she was called “Lady of the West” or “Western Mountain,” referring to the west bank of the Nile.Her prominent role in funerary images and rituals was closely linked to her role in promoting fertility. Hathor, as the night sky, is believed to have received Ra every night on the western horizon and protected him within her body so that he could safely give birth each morning.

Based on this divine model, Hathor was seen as the source of rebirth and renewal for all the dead, royal and non-royal, and they all hoped to receive similar protection from her.

Hathor at Sinai

She was also worshipped in the copper mines on the eastern edge of the Sinai Peninsula. Hathor's popularity extended beyond Egypt to foreign cities, where she was worshipped as the “Lady of Byblos” in that city on the eastern coast of the Mediterranean Sea.

Because the prehistoric cow worship from which Hathor's cult evolved was found throughout the country, it is difficult to pinpoint her original center of worship.

Her cult may have originated in the Delta region, where her son Horus also had an important role and her cult emerged in the Kom el-Hisn region in the north of the country.

Hathor Worship Centers

Dendera in Upper Egypt was an important early site for Hathor, where she was worshipped as the “Lady of Dendera (Ionet)”.Her worship also appeared in scattered areas in southern Egypt. Based on the distribution of titles within her cult, the Giza-Saqqara region appears to have been the center of worship in the Old Kingdom. However, by the First Intermediate Period, this focus shifted south, and Dendera has since emerged as the center of Hathor's worship.

|

| The Temple of Hathor at Dendera, photographed in 2006 by Steve F-E-Cameron (Merlin-UK), licensed under GFDL and CC BY 2.5. |

At Dendera Hathor was in close relationship with Horus at Edfu, a nearby site.

In this case she was not Horus' mother but his wife, and bore him two children, Ehi and Harsomtus. Deir el-Bahri, on the west bank of Thebes, was also an important cult site for Hathor.

The area was the site of a famous cow cult before the Middle Kingdom. This cow goddess was identified as Hathor in the Eleventh Dynasty.

In the New Kingdom, Hatshepsut and Thutmose III built their funerary temples at Deir el-Bahri, and both temples included shrines to Hathor. Hathor was worshipped as a cow at this site, and the funerary temples were decorated with bas-reliefs of the king suckling Hathor as a cow. The stories of Hathor in mythology reflect both her diverse and mysterious nature.

|

| Breastfeeding of Hatshepsut by Hathor, Hatshepsut Temple, Deir el-Bahari, Egypt. Photo by Rémih, taken on 13 June 2009, licensed as own work. |

Hathor in mythology

There is an unusual myth, whose meaning is uncertain, that clearly refers to her sexuality.In the conflicts of Horus and Set, Hathor approaches the troubled Ra and exposes her body to him, making the god laugh.

Two other well-understood myths involving Hathor and Ra reveal the duality of Hathor's nature, which oscillates between joy and destruction. In the story of the destruction of humanity, the elderly Ra, who rules the earth, sends Hathor to punish his rebellious subjects.

When Ra witnesses the destruction wrought by Hathor, he regrets his decision and tries to prevent her from continuing, flooding the earth with beer dyed to resemble blood, to which Hathor is attracted.

She gets drunk, unharmed, and the people survive. Based on this myth, Hathor was also worshipped as the goddess of drunkenness.

In a second myth, Hathor is described as a lioness in the Nubian desert. Ra sends Thoth to bring her to him for protection.

Upon their return, Thoth immerses the lioness in the cold waters of the Nile in order to calm her ferocity, making her calm and cheerful.

These myths illustrate the aggressive and destructive aspects of Hathor that were an integral part of her overall personality.

In this aspect she was associated with the goddess Sekhmet, the destructive female lioness of the Nubian desert.

The transformation of the goddess from a destructive aspect to a calm and cheerful one was essential for the Egyptians in preserving their lives and their country, and thus festivals dedicated to Hathor included excessive drinking along with music and dancing with the intention of pacifying the great goddess.

Hathor and kingship

Hathor was understood to be the mother of Horus, based on a metaphorical reading of “whale” as “womb,” and since Ra surpassed Horus in mythology, especially in terms of kingship, Hathor has been described as Ra's mother as well.She also absorbed this role from another cow goddess, Mehet-Weret of Great Flood fame, who in the creation myth was Ra's mother; she gave birth to the sun god and carried him between her horns, an iconographic element later adopted by Hathor.

Hathor's importance in the institution of kingship was solidified from its earliest stages. Because Horus was the first royal deity, Hathor symbolically became the divine mother of the pharaoh.

She is often depicted in this role as a cow, which relates to a myth where baby Horus was hidden from his murderous uncle Set in the marshes, where he was suckled by the divine cow.

The image of Hathor as a cow suckling the pharaoh was common in the New Kingdom, emphasizing the divine aspect of the king, and Hathor was worshipped as a cow in Deir el-Bahri.

|

| Hathor Chapel at the Temple of Thutmosis III, Deir el-Bahari. Photo from 1907 excavation by Henry Edouard Naville now in the Egyptian Museum, Cairo (JE 38574-5). |

At the top of the painting is the king's name surrounded by two cow heads - perhaps the god Bat in this case, but because of Bat's close relationship and eventual submission to Hathor, this can be considered essential to Hathor's personality as well.

✨ Symbols & Roles of Hathor ✨

Cow Horns + Sun Disk

Symbol of motherhood, solar power, and divine beauty.

Sistrum

Ritual rattle for music, joy, and temple ceremonies.

Menat Necklace

Protective amulet symbolizing renewal and feminine power.

Royal Mother

Patroness of queens and divine mother of the pharaoh.

© historyandmyths.com — Educational use

Hathor in rituals and festivals

Hathor also appears in relation to the king in pyramid texts, where the king is said to perform a ritual dance and shaking in the worship of Hathor.Sculptures depicting the king with Hathor appear as early as the reign of Menkaure and are common during the later periods.

In addition, Hathor played an important role in the Sed festival, the royal ritual dedicated to the king's symbolic rebirth, as evidenced by bas-reliefs in the Kheruef tomb depicting the Sed festival of Amenhotep III. The rituals in honor of Hathor are often enacted in music and group dance.

|

| Exhibit at the Harvard Semitic Museum, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA. Photo by Daderot, April 3, 2016. Public domain. |

As the Old Kingdom begins, we find many tomb scenes showing dancers performing with musicians in her honor.

In Thebes, the integrated music and dance of the Valley Festival, a celebration that brought relatives to the tombs of their deceased family members on the West Bank, was performed under the patronage of Hathor.

Hathor's two most recognizable and sacred objects were the musical goddess Sistrum and the necklace of Manat, which could be shaken like Sistrum; both were used in dance and music rituals.

|

| Menat necklace from Malqata, reign of Amenhotep III (1390–1353 B.C.) New Kingdom, Dynasty 18. Made of faience, glass, and semi-precious stones. Metropolitan Museum of Art, Accession No. 11.215.450 |

|

| Faience sistrum inscribed with the name of Ptolemy I, Ptolemaic Period (305–282 B.C.), H. 26.7 cm. Metropolitan Museum of Art, Accession No. 50.99. |

A related ritual was the papyrus shaking ritual, which is said to be performed by the king in pyramid texts and depicted in the tombs of many individuals as well.

The shaking of papyrus plants sacred to Hathor is related to the shaking of the sistrum. The king would also dance for Hathor during his feast, as written in the bas-reliefs on the tomb of Kheruef.

The calendar in the Temple of Dendera lists more than twenty-five festivals celebrated for Hathor. Many of them took place under her patronage, while others were celebrated especially for her.

On New Year's Day, her cult statue was brought to the roof of her temple so that she could unite with Ra in the form of sunlight, an act that also occurred on other festival days.

On the twentieth day of the first month, Egyptians celebrated the Sugar Festival in her honor, and in the spring there was another festival in her honor related to the legend of her return from the Nubian desert.

Conclusion

Hathor was one of the most complex and enigmatic Egyptian goddesses, and also one of the most enduring.Her status as a prehistoric goddess makes it almost impossible to pinpoint her origins, and it is also difficult to untangle the many aspects and myths that make up her persona.

However, it is clear that she played a vital role in Egyptian society from the highest to the lowest levels, essential to the identity and personality of the king and the favorite goddess of the common people, who flooded her local cults with offerings and prayers.

Frequently Asked Questions about Hathor

1) Who is Hathor in Ancient Egyptian religion?

Hathor is the goddess of love, beauty, music, joy, fertility, and protection—also revered as “Lady of the West” in funerary tradition.

2) What are Hathor’s main symbols?

Cow horns with a solar disk, the sistrum (ritual rattle), and the menat necklace; she also appears as a cow or a woman with cow’s ears.

3) Where was Hathor primarily worshipped?

Dendera was her principal cult center, though her worship spread widely across Egypt, including Thebes.

4) What is the Festival of Drunkenness?

A celebratory rite linked to Hathor’s “Eye of Ra” tradition—marking joy, renewal, and the triumph of life after chaos.

5) How is Hathor connected to kingship?

She is the symbolic mother of the pharaoh; queens adopted her headdress, and music/dance rites honored her in court and temple.

6) Is Hathor the same as Isis or Sekhmet?

No—while they can overlap in roles (motherhood, Eye of Ra), Hathor’s identity centers on love, beauty, music, and joyous renewal.

References

- Wilkinson, Richard H. The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson.

- Hornung, Erik. Conceptions of God in Ancient Egypt: The One and the Many. Princeton University Press.

- Pinch, Geraldine. Egyptian Myth: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press.

- Assmann, Jan. The Search for God in Ancient Egypt. Cornell University Press.

- Shaw, Ian (ed.). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press.