Role of Festivals in Ancient Egyptian Religion

Festivals in ancient Egypt played a significant role in the official religious practices of the Nile Valley. Evidence of these celebrations is preserved in both visual and textual records. Numerous liturgical texts, including hymns and prayers, have allowed researchers to reconstruct the arrangements and settings of these events.Calendrical Classification of Egyptian Festivals

These festivals can often be categorized from a calendrical perspective, as most were fixed within the civil calendar. They occurred on specific days or spanned several days throughout the year. Referred to by scholars as "annual festivals," these events began with Wep-renpet, the Egyptian New Year’s Day, which marked the start of the civil calendar and symbolized renewal and rebirth.Wagy Festival: Mortuary Rituals

Seventeen days after Wep-renpet, during the first month of the year, the more solemn Wagy feast was observed. Later associated with the festival of Thoth on the nineteenth day, Wagy was deeply tied to Egypt’s mortuary rituals. This festival was celebrated both privately, outside official cultic settings, and in the grand temples across Egypt. Records of this festival date back to the Fourth Dynasty, as evidenced by private feast lists inscribed in tombs. Interestingly, Wagy maintained its original lunar connection, resulting in two separate observances: one based on the lunar cycle and the other fixed on the eighteenth day of the first civil month. |

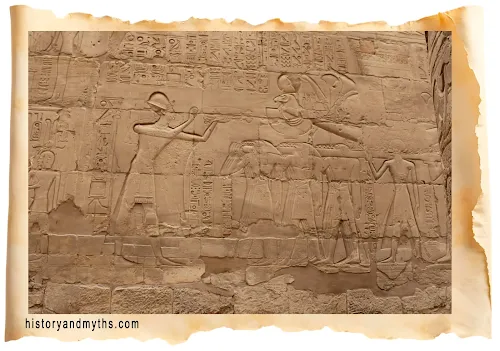

| Opet Festival |

Opet Festival: Pharaoh’s Divine Authority

In the second civil month, the grand Opet festival of the New Kingdom became prominent. This celebration was closely associated with the pharaoh and the deity Amun (or Amun-Re). Tied to the lunar cycle, the festival featured a journey by the pharaoh-to-be to Luxor’s temple in Thebes, where Amun would endow him with the divine authority of kingship, embodying the living Horus. By the New Kingdom, this event firmly linked Amun and the pharaoh within the state religion, reflecting its rising importance as evidenced by its 27-day duration in the Twentieth Dynasty. However, no references to Opet exist prior to the Eighteenth Dynasty, suggesting that Thebes' emergence as a national power elevated Amun to a state deity. Through this festival, Amun’s might and authority were symbolically transferred to the king, solidifying the pharaoh's role within royal ideology. Notably, the event included the pharaoh’s ceremonial visit to Luxor for his coronation.Sokar Festival and Afterlife Beliefs

Another major festival, equal in significance to Opet but much older, was the Choiak or Sokar feast, celebrated during the fourth civil month. This festival highlighted the enduring prominence of Osiris, the god of the afterlife, and his connection to Memphis’s ancient powers, particularly through the deity Sokar. Unlike Opet, the Sokar festival is known to date back to the Old Kingdom, reflecting Memphis’s importance after it became Egypt’s capital. Sokar’s presence in private feast lists of the Old Kingdom confirms its early significance. The deity himself likely predates Egypt’s unification and the establishment of Memphis as its capital during the First Dynasty, emphasizing the festival's deep historical roots.By the Late Period, the duration of the Sokar festival had expanded significantly from its original span of six days (the 25th to the 30th of the fourth month). In many respects, this festival marked the conclusion of the first season of the Egyptian year, the Inundation, as the first day of the following month symbolized the beginning of a new era. The final days of the fourth month, often observed with grief and solemnity, became closely associated with Osiris, who was believed to have died on the central day of the Sokar festival, the 26th of the fourth month.

|

| Sokar Festival |

New Year Festivals and Rebirth Themes

Unsurprisingly, the first day of the fifth month introduced a symbolic New Year of rebirth, known as Nehebkau, just five days after Osiris’ death. The intervening days were seen as a time for the god’s eventual resurrection, later tied to the king’s rebirth as the living Horus. Nehebkau mirrored the calendrical New Year on the first day of the first month, with many of the same rituals and ceremonies being performed on both occasions.Fertility Festivals and Agricultural Cycles

Two other major annual celebrations deserve mention. The first, the festival of the fertility god Min, marked the start of a new season in the ninth civil month and was determined by the lunar calendar. This ancient festival, primarily documented from New Kingdom and later sources, emphasized the pharaoh’s role as the sustainer of life. The king would ritually cut the first sheaf of grain, symbolizing the fertility and vitality of the land. The four corners of the universe held special significance during this celebration, which underscored themes of rebirth and abundance tied to Min’s association with fertility. This festival, deeply rooted in agricultural cycles, was fundamentally a celebration of renewal.The tenth month featured the renowned Feast of the Valley, another Theban festival with origins in the Middle Kingdom that gained prominence during the New Kingdom. During this celebration, the statues of Amun, his consort Mut, and their son Khonsu were transported from Karnak across the Nile to Deir el-Bahri on the western bank. Notably, inscriptions in private Theban tombs show that this feast was a time for families to honor their deceased relatives by visiting their tombs. These private customs bear a striking resemblance to modern traditions in Egypt and other cultures, where people gather in cemeteries to commemorate their ancestors.

Major Annual Festivals in Ancient Egypt

Throughout the Nile Valley, countless local religious sites existed alongside the nation’s major cultic centers. Based on surviving records, a detailed calendar of rituals and feasts for Egypt’s major deities—such as Amun of Thebes, Hathor of Dendera, and Horus of Edfu—can be reconstructed. Many temples have walls inscribed with systematic lists of festivals, which were copied from official temple archives. These calendars reveal whether a feast was aligned with the civil calendar or based on lunar cycles. Additionally, regular lunar observances occurred, one for each lunar day, distinct from the annual festivals. These "seasonal festivals" were deliberately separated from the yearly celebrations previously mentioned.Secular Celebrations and Ramesses III's Victory

Rarely do we find records of festivals commemorating secular events, as most information pertains to religious or cultic celebrations. However, there are a few notable exceptions. One such instance is the annual celebration initiated by Ramesses III to mark his victory over the Libyans (the Meshwesh), who had unsuccessfully attempted to invade Egypt during his reign. Another example is the king’s coronation, an event that was typically included in religious calendars. Additionally, the Heliacal Rising of Sothis (the star Sirius) stands out. While there was no formal cult dedicated to Sothis, this astronomical event was highly significant. The reappearance of Sothis after seventy days of invisibility originally heralded the New Year and came to symbolize the ideal rebirth of the land.Heb-Sed Festival: King's Rejuvenation

Another long-standing celebration, not often mentioned in festival calendars, is the king’s rejuvenation festival after thirty years on the throne, known as the heb-sed. This event, secular in nature, centered on renewing the vitality and strength of the pharaoh. Its origins are shrouded in mystery, though it likely dates back to Predynastic times. Extensive inscriptions and artwork provide evidence of the heb-sed, suggesting it may have been tied to lunar cycles, as thirty years aligns with the duration of a lunar month (thirty days). One of the key rituals of this festival was the Raising of the Djed-Pillar, a symbol of rebirth and closely associated with Osiris. This act paralleled the Choiak feast, which marked the death of Osiris, and underscored the pharaoh’s connection to life and renewal.Numerous depictions of the heb-sed have survived. Important examples can be found in the sun temple of Newoserre Any, the tomb of Kheruef at Thebes, the temple of Amenhotep III at Soleb in Nubia, Akhenaten’s East Karnak Temple, and even in records from the Saite period (26th Dynasty). These sources allow us to reconstruct key aspects of the festival, including the elaborate ceremonial palaces built specifically for the occasion and the intricate attire worn by participants, including the king himself. These elements highlight the festival’s deeply rooted and ancient traditions.

Economic Resources for Major Festivals

Economic records from temple archives provide additional insights into these events. By examining such documents, scholars have been able to estimate temple wealth and the number of priests required to maintain the cult. Major festivals, like the Sokar (Choiak) and Opet celebrations, required substantial resources, often involving large quantities of food and other offerings. The duration of these festivals, noted in calendars, was rarely brief, and special provisions were made for temple priests during events like the king’s accession anniversary. Records from temples like Medinet Habu help illustrate the scale of resources needed, including the number of officiating priests.Temple Wealth and Administration in the Middle Kingdom

Beyond the extensive data from New Kingdom festival calendars, papyri from Middle Kingdom temple sites, such as those from Iahun, offer a glimpse into the economic workings of religious institutions. These documents, dating to the reigns of Senwosret III and Amenemhet III, provide details about the mortuary temple of Senwosret II. Unlike the major temple estates of the New Kingdom, these Middle Kingdom temples were smaller operations, with personnel likely numbering no more than fifty. Their modest incomes are documented in daily records, which also outline monthly priestly rotas and the division of the priesthood into phyles—a system that originated in the Old Kingdom. These texts meticulously record the festivals, the quantities of food offerings, their delivery times, and the exact schedules for ceremonies, giving us a clearer picture of the day-to-day functioning of these institutions.From accounts like these, it becomes clear just how extensive a temple's wealth could be and who contributed to its upkeep. Supporting the cult required offerings, and these offerings had to come from somewhere—primarily land, which was essential for sustaining a temple's economic foundation. For instance, some New Kingdom festival calendars (though not all) specify the sources of the food offerings and reference the tenant farmers and gardeners responsible for cultivating these provisions. Studies of land-owning institutions in ancient Egypt further help us piece together the scale of agricultural territory owned by certain temples, as well as the revenues they collected from the agricultural laborers leasing land from these religious corporations. It’s evident that the wealth of prominent temples, like Karnak, had grown considerably since the Middle Kingdom. The practice of “reversion of offerings,” where food presented to the gods was later redistributed (often unequally) among the temple’s clergy, highlights not only the significance of various festivals but also the tangible benefits enjoyed by the priesthood.

Public Participation in Major Festivals

However, one major question remains unresolved in our understanding of these celebrations: the broader nature of ancient Egyptian religious thought. On one hand, major festivals such as Opet or the Valley Festival are relatively straightforward to analyze. Festival calendars, along with associated texts and images, reveal the involvement of key non-royal figures and officials alongside the priests conducting the rituals. Temples from the Greco-Roman period, like those at Edfu and Dendera, even provide detailed accounts of the gods’ ceremonial voyages. The intricate mythology surrounding Horus of Edfu and his connection to Hathor of Dendera suggests a more public dimension to these events than the formal, programmatic entries found in festival calendars. Similar evidence is reflected in depictions and records of other grand celebrations, including Opet, the Valley Festival, and the heb-sed rituals.In many instances—Opet being a prime example—the participation of individuals outside the priesthood is evident. This becomes particularly apparent in descriptions of the processions held during these festivals, as they often extended beyond the temple precincts, making the gods more visible to the public. Such rare appearances of the deities in open spaces had significant implications, often intensifying religious devotion. For example, oracles frequently took place during these processions, with priests and sometimes larger audiences present. Records indicate that these divine consultations, whether favorable or otherwise, were fairly common. Local or regional gods were often approached by private individuals seeking guidance or revelations, while some oracles played a role in public matters—like appointing a high priest of Amun. In these cases, the gods’ decisions were inscribed on temple walls or stelae for public record. For more personal matters, such as disputes or theft, the decisions were documented on ostraca or papyri.

One notable example of divine judgment came from the local chapel of the deified Amenhotep I on the western bank of Thebes. This shrine was frequently consulted by workmen in the area to resolve disputes or provide rulings on contested issues. Oracles were especially common on significant feast days when the god was carried out beyond the temple walls, emphasizing the unique connection between divine will and public life during these grand celebrations.

Public vs. Private Aspects of Temples

The distinction between the public and private aspects of the temple is crucial and should not be underestimated. From the early dynastic mortuary temples, the Old Kingdom saw the accumulation of both wealth and religious significance for these cults. Whether tied to the king's mortuary temple or to a god, like the sun temple dedicated to the solar deity Ra, these religious institutions were economically and socially significant. However, they were often self-contained and more reserved, rarely inviting public participation or fervor. This trend continued into the Middle Kingdom, as seen in the account papyri from Iahun, which illustrate how separated the temple's life was from the town’s daily life.By the New Kingdom, however, things began to shift. Major public celebrations took place, which were witnessed by outsiders. People gathered as the god Amun traveled from Karnak to Luxor, crossed the Nile to visit Deir el-Bahri for the Valley festival, or made his way to Medinet Habu for the Opet festival. These were moments of public spectacle, and during them, oracles could be given, marking both public and private celebrations. Likewise, when Hathor of Dendera visited Horus of Edfu, the streets were filled with people in a festive atmosphere.

While this external, public aspect of the cults should not be overlooked, much of the action within the temple walls was private and secretive. Daily rituals held at morning, noon, and evening were not open to the public, and even important nonroyal figures could rarely move beyond the temple's outer courts. The inner sanctum of the temple, often dim and private, was reserved for specific purposes and kept distinct from the public spaces. Even when the king underwent a rejuvenation ritual in Luxor, the common townspeople remained outside the temple. Access to a temple and participation in its ceremonies were privileges granted to only a few.

This distinction has led scholars to describe two types of religion in ancient Egypt: “official” or “cultic” religion, and “popular” religion. The official religion is well-documented, reflected in the monumental temples, inscriptions, and reliefs, as well as liturgies and mythological texts preserved on papyri. These sources focus heavily on the major gods and the pharaoh, providing insights into the religious practices of the elite and important nonroyal figures. However, they do not reveal much about the daily religious life of the average Egyptian. Private cults, for example, did not interfere with the grand state temples, and the smaller, less elaborate shrines associated with state gods were not as significant in the broader religious narrative.

Archaeological discoveries have uncovered many personal religious practices that existed alongside the official cults. Small offering tables and votive stelae dedicated to individual deities have been found in homes and courtyards. Despite this, little is known about the private festival practices of the average Egyptian. Records, mostly on ostraca or papyri from the late New Kingdom, suggest that personal devotion was a strong sentiment in ancient Egypt, though it is not frequently represented in official records. Even the famous Middle Egyptian literary work, the Story of Sinuhe, underscores the protagonist’s relationship with his personal god, whose name remains unspecified. Amid all this, the few private oracles recorded in these sources are among the rare instances where we can link personal worship to a festival.

The major temples of ancient Egypt were largely disconnected from the lives of the average Egyptians. Mortuary temples, which were mainly located on the west side of Thebes during the New Kingdom, were constructed to honor the pharaoh as a divine figure both during his lifetime and after his death. This tradition dates back to the Early Dynastic period, with a separate cult for the pharaoh clearly existing even then. The establishment of these temples was typically a royal initiative, with the king determining their activities shortly after ascending the throne. In the Old Kingdom, such temples played a dominant role in official religious practices, exemplified by the monumental pyramids built during the Third through Sixth Dynasties. Other temples, however, were more local and smaller, such as those dedicated to Min or the chapels at Abydos. Except for the Osiris temple at Abydos, major religious structures were relatively rare in the Nile Valley until the Fifth Dynasty. During this period, the pharaohs began constructing sun temples dedicated to the solar god Re, their theological ancestor, signaling a significant shift in the religious landscape. However, this practice ended by the close of the Fifth Dynasty, and for the remainder of the Old Kingdom, the focus returned to the king’s mortuary temples.

By the Middle Kingdom, while smaller temples persisted, they were larger and more complex than in previous periods, as seen in the expansion of the temple of Satet at Elephantine. However, mortuary temples remained largely self-contained economic units. A significant change occurred with the rise of Thebes and the expansion of Amun's cult during the late Second Intermediate Period. By the early Eighteenth Dynasty, the pharaohs began transforming Amun's temple at Karnak from a wooden structure into a massive stone edifice, adorned with pylons and richly detailed walls that depicted historical and religious narratives. The wealth and power of Egypt, particularly during the height of the Eighteenth Dynasty, enabled ambitious temple-building projects both in Egypt and Nubia. One notable example is the grand temple of Soleb in Nubia, constructed by Amenhotep III, along with the many grotto temples of Ramesses II in the southern regions.

Karnak, Luxor, and the temples at Memphis were major religious centers maintained by the pharaohs. The Nineteenth and Twentieth Dynasties saw continued additions to the key temples at Thebes, Memphis, and Heliopolis. In Western Thebes, mortuary temples continued to be aligned along a north-south axis, though by the end of the New Kingdom, shifts in the importance of the cults became evident. During the Third Intermediate Period, cultic expansion ceased at most locations except Karnak. As Amun-Re gained dominance in the south and his high priest assumed control over the region, other Egyptian cults lost significance. It wasn’t until powerful dynasties such as the Kushite (Twenty-fifth) and Saite (Twenty-sixth) dynasties that the importance of these religious institutions began to rise again. By the Twenty-sixth Dynasty, the focus of religious activity shifted to the north, particularly in the city of Sais, the seat of power for that dynasty.

Ptolemaic Period Religious Practices

With the arrival of the Greeks and Macedonians, local cults continued their religious practices, but they became increasingly marginalized in comparison to the grandeur of past eras. The Ptolemaic kings, though recognized as pharaohs, were primarily worshipped as rulers in temples like those at Edfu and Esna. However, these temples did not enjoy the immense wealth that had once supported Amun-Re at Karnak. Consequently, the festival calendars from this period do not detail the offerings or the specific lands managed by the temples, which had previously been a key source of revenue.Our understanding of religious festivals during the Ptolemaic period is mostly derived from private papyri and funerary stelae, which suggest that many of the traditional religious celebrations had faded or even disappeared. The Opet festival still occurred but had significantly declined in importance, while the cult of Osiris continued to be practiced across the land, as attested in Plutarch's famous work on Isis and Osiris.