What do ancient Egyptian tombs reveal about their beliefs?

Numerous tombs of different dates and styles, many of which contain carefully prepared bodies as well as a variety of funerary items, reveal the ancient Egyptians' belief in life after death. The decorations in some tombs, in color or bas-relief, include depictions of burial rituals. Some texts from the corpus of ancient Egyptian literature talk about the view of the afterlife and emphasize the need to make offerings for eternity.

_-_Neues_Museum,_Berlino.webp) |

| Sarcophagus of Ken-Hor – Akhmim-Sohag. 26th Dynasty (around 600 BCE) – Neues Museum, Berlin | Date: 20 August 2019, 14:55:35 | Source: Own work | Author: Raffaele Pagani |

How were ancient Egyptian tombs constructed?

This archaeological, artistic and textual evidence shows that burial practices were centered around three events: The construction of the tomb; the burial of the body; and the performance of devotional rituals to allow the deceased to reach the afterlife and remain there forever.

What are the different components of ancient Egyptian tombs?

With the exception of monuments, such as those built during the Middle Kingdom at Abydos, ancient Egyptian tombs were designed to contain at least one body. Tombs were usually built during the owner's lifetime to be ready when they died. Tombs were usually built in groups with other tombs of similar date and class, within tombs located in the desert. Most tombs are located on the west bank of the Nile River.

How did royal tombs differ from non-royal tombs in ancient Egypt?

Tomb structures can generally be divided into three components: The superstructure; the substructure, which often includes the burial chamber; and the opening or corridor that connects the above- and below-ground structures. Originally, not all tombs had all three components, and some tombs were partially destroyed in the centuries after they were built. However, there are still tombs that are well enough preserved to prove that the style of tombs changes over time, and the size of the tomb and the degree of decoration often also reflect the relative wealth and status of the tomb's owner. Since the king was the most powerful member of society, royal tombs are the most elaborate known in ancient Egypt, often showing different forms than those found in non-royal tombs.

|

| Tomb of Senefer in Luxor| Date: 31 August 2005 | Source: flickr | Author: kudumomo |

What are the earliest types of tombs found in Egypt?

The earliest Predynastic tombs, such as those in the Meremda necropolis in the Nile Delta, consisted of simple oval or round pits hollowed out of sand, where the body was placed in a shrunken position; sometimes mounds of sand characterized the positioning of these tombs. More elaborate tombs, presumably belonging to wealthy and high-status individuals, were developed as early as the late pre-dynastic period. A tomb of that date at the site of Hierakonpolis includes a large mud-brick chamber, the western wall of which is painted with scenes of ships and fishermen.

How did tombs develop during the Early Dynastic period?

Abydos, the site of the tombs of the First Dynasty kings and the tombs of the last two Second Dynasty kings, provides clear evidence of the development of royal tomb types during the Early Dynastic period. The Early Dynasty royal tombs at Abydos consist of two structures located at a distance from each other. Near the cliffs of Umm al-Ja'ab, where the kings' bodies were placed, large underground mud-brick chambers supported and roofed by wooden pillars. The superstructures of these tombs had sacrificial niches on their eastern sides, in which monuments were placed. Surrounding the royal tombs at Umm al-Ja'ab were small mud-brick tombs built for the king's servants, some of whom were sacrificed upon the death of their ruler; Egyptians abandoned this practice before the end of the Second Dynasty. Near the Nile at Abydos, large mud-brick tombs were built and contained cult buildings.

|

| Umm El Qa'ab |

What role did pyramids play in ancient Egyptian burial practices?

In the Old Kingdom, the development of royal tomb types continued with the construction of the most famous type of royal tomb in Egypt, the pyramid. At the most basic level, pyramids are the most prominent element in the construction of royal tomb complexes in the Old or Middle Kingdom. The large-scale stone pyramid complexes at Giza for the Fourth Dynasty kings Khufu, Khafre, and Menkaure are the most famous; the main pyramid of these complexes contained the king's burial chamber, while smaller pyramids near the main pyramid included the burials of royal wives. Elements of these pyramid complexes that emphasized the importance of ritual worship in royal burials included a chapel built next to one side of the main pyramid, a valley temple built near the edge of the river, and a bridge connecting the two. The beginnings of many of the elements of these pyramid complexes can be seen in the stepped pyramid complex of King Djoser of the Third Dynasty at Saqqara. Around the pyramid complexes, many tombs of Old Kingdom officials were clustered.

What is a mastaba tomb and how was it used?

Mastaba tombs have been known since the First (Old) Dynasty, such as Saqqara; they are a free-standing rectangular superstructure constructed of mud brick or stone, containing one or more chambers. The burial chamber is located underground. One of the inner walls bears a false door - a carved image of a chiseled entrance. An offering table was placed on the floor of the mastaba in front of this entrance, and the ka, a spiritual aspect of the deceased important for his nourishment, would come to the false door to participate in the offerings. Some mastaba tombs have highly ornate superstructures - the Saqqara mastaba of Meroka, a minister under King Teti of the Sixth Dynasty, is famous for its large size and intricate relief decoration. Texts inside these mastaba tombs often indicate that they or parts of them were given to officials as gifts from the king. The construction of mastaba tombs continued into the Twelfth Dynasty, but by the First Intermediate Period most private tombs were of the rock-cut type.

Around the pyramid complexes, many tombs of Old Kingdom officials were clustered. Mastaba tombs have been known since the First (Old) Dynasty, such as Saqqara; they are a free-standing rectangular superstructure constructed of mud brick or stone, containing one or more chambers. The burial chamber is located underground. One of the inner walls bears a false door - a carved image of a chiseled entrance. An offering table was placed on the floor of the mastaba in front of this entrance, and the ka, a spiritual aspect of the deceased important for his nourishment, would come to the false door to participate in the offerings. Some mastaba tombs have highly ornate superstructures - the Saqqara mastaba of Mereruka , a minister under King Teti of the Sixth Dynasty, is famous for its large size and intricate relief decoration. Texts inside these mastaba tombs often indicate that they or parts of them were given to officials as gifts from the king. The construction of mastaba tombs continued into the Twelfth Dynasty, but by the First Intermediate Period most private tombs were of the rock-cut type.

How were tombs decorated in ancient Egypt?

The main chambers of many Middle and New Kingdom tombs of officials were carved into the cliffs overlooking the Nile Valley. The New Kingdom tombs at Thebes include many rock-cut tombs with underground burial chambers, connected to each other by a vertical or stepped shaft.

Although today many of the rock-cut tombs do not often have built superstructures, the Raamesside tombs of the artisans at Deir el-Medina often had very small pyramidal superstructures. The superstructures at Deir el-Medina were sometimes decorated with rows of funerary cones - cone-shaped objects of baked clay whose flat ends were often stamped with the tomb owner's name and titles.

|

| Tomorrow at the entrance to the city of Medina, near the country, Egypt | Date: 13 June 2009 | Source: Own work | Author: Rémih |

New Kingdom rulers had rock-cut tombs dug into the west bank of the Nile at Thebes in the Valley of the Kings, where the surrounding cliffs create a natural pyramidal crest. Tombs in the Valley of the Kings often extended deep into the cliff face, encompassing numerous corridors and chambers The lack of a man-made superstructure may reflect the architects' attempts to make these royal tombs less visible than previous royal tomb complexes, and thus safer from tomb robbers. Since the locations of the tombs in the Valley of the Kings were supposed to be unknown, funerary offerings had to be made elsewhere.

|

| Valley of the Nobles, Theban Necropolis, Egypt | Français: Vallée des Nobles, nécropole thébaine, Égypte | Date: 8 June 2009 | Source: Own work | Author: Rémih |

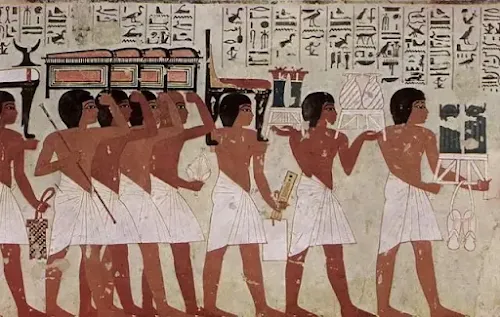

After the tomb was built, it was often decorated. Tombs were decorated with flat painted scenes or carved scenes. In the Old and Middle Kingdoms, tomb scenes included the activities of the tomb owner and his family. For example, they were depicted fishing in the marshes. Some tombs in the Old and Middle Kingdoms included small clay or wooden figures engaged in activities similar to those on the walls. In the late New Kingdom, only scenes depicting aspects of the afterlife, such as tomb owners worshipping different gods, were used. Most of the earlier decorated tombs showed the deceased receiving offerings: In many Old Kingdom tombs, the owner of the tomb is shown sitting on a chair in front of a small table. On and around the table are all kinds of food offerings - bread, jars containing liquids and pieces of meat. Processions of people carrying similar offerings also appear in many tombs.

Sometimes tomb decorations included scenes of the burial itself. The 18th Dynasty tomb of Camus, for example, has on one of its walls a painting of a funeral procession carrying the owner's funerary belongings to his tomb, which included weeping women throwing sand on their heads in a gesture of mourning and men carrying boxes and pieces of furniture. The scenes in the tomb also depicted the rituals that took place in the tomb, such as the mouth-opening ceremony.

The texts accompanying the decorative scenes in the tombs ranged from short inscriptions identifying individuals or their actions and words to long biographical texts describing the life of the owner of the tomb. Many of the tomb texts concerned offerings, with the name of the deceased and a list of objects following an introductory statement emphasizing that the offerings came from the king or a god. The offerings were detailed in a list, which appeared on the wall of the tomb, often near the false door. These lists detailed the names of goods desired by the deceased, including items for the tomb and foodstuffs.

What was the process of mummification in ancient Egypt?

The process begins with the death of the owner and the preparation of the body. In Prehistoric burials, bodies were not artificially preserved; the effect of the hot sand in which they were placed was often enough to ensure a certain degree of preservation. Prehistoric bodies were usually placed on the left side, with their faces facing west. In ancient times, the finding of some naturally preserved bodies, due to the shifting desert sands, may have reinforced the Egyptians' belief that the preservation of the body was essential for life after death. In the Early Dynastic period, the development of more ornate tomb structures and the use of sarcophagi separated the body from the surrounding sand. The artificial preservation of the body - mummification - became necessary.How were canopic jars used in mummification?

In the Old Kingdom, a corpse from the Second Dynasty is known with evidence of primitive mummification techniques. The process was perfected in the embalming workshop, and by the New Kingdom, mummification steps included removing the brain, eviscerating the body (except for the heart, which was left in place), drying the body with a salt mixture, and drying the internal organs separately. After the Fourth Dynasty, the lungs, liver, stomach, and intestines were each placed in a vessel; these canopic jars were sometimes placed inside a canopic box. By the early Middle Kingdom, the four canopic jars were believed to have been protected by the four demigods called the Sons of Horus. After the body was sufficiently dry, it was wrapped in pieces of linen. During the Greco-Roman period, the wrappings on mummies showed highly ornate patterns, yet the bodies inside were often poorly preserved. Amulets were sometimes placed between the scrolls to help protect the deceased. The entire mummification process took about seventy days. When completed, the mummy was usually placed inside a coffin, usually rectangular or anthropomorphic (human-shaped), or, especially in the case of royal burials, surrounded by a sarcophagus. Coffin designs often provided information about the date of burial.

|

| Canopic Jar of Ruiu - A canopic jar with a human-headed lid representing Qebehsenuef, dated to circa 1504–1447 B.C. during the early 18th Dynasty of the New Kingdom. Made of pottery and paint, it measures 33 cm in height (jar: 24.5 cm, lid: 11 cm). Part of the Metropolitan Museum of Art collection (Accession Number: 35.3.36a, b), it was discovered in Thebes, Asasif, in the Tomb of Neferkhawet during MMA excavations (1934–35). Source: The Met Museum. |

What rituals were performed after mummification?

Scenes and inscriptions from various tombs from Pharaonic times illustrate the rituals that took place after the body was prepared. The mummy received food offerings in the “hall of purification” and was then carried in procession to the ritual places and then dragged on a stretcher to the tomb, the procession including the canopic box. At the grave, offerings were made and a bull was slaughtered. The priests then recited words of protection for the deceased, whose mummies were placed in the burial chamber.

What types of funerary items were placed inside tombs?

In addition to the mummy, funerary items were usually placed inside tombs and could be used by the owner while alive, while some were designed for use in the tomb and the afterlife only. Analyzing grave goods provides glimpses into how Egyptians viewed the afterlife. The primary grave goods found in the tombs of all pharaonic periods were ceramic vessels for food and beverages such as bread, beer or wine. Other vessels, such as stoneware and, especially in the New Kingdom, faience, could also be included among the funerary goods. Some tombs included clothing and objects of personal adornment, such as kohl pots for eye makeup and jewelry made of gold and silver and semi-precious stones. Wooden furniture such as chairs and headrests used for sleeping may be placed in the tomb. Weapons (such as daggers) and tools (such as chisels and axes) were also placed in the tombs. All of these objects were identical or identical to those that the deceased owned during life and suggest that the basic necessities of life on earth were required in death.

What are funerary statuettes and offering tables?

Other types of funerary objects were made only for use in the tomb. Early Mesolithic and sometimes later tombs contained small statuettes, often depicted holding agricultural implements such as hoes, and sometimes inscribed with text describing their tasks. Funerary statues or ushaptis were designed to work on behalf of their owner in the afterlife. Offering tables, often inscribed with texts, were also made to be placed in the tomb. The presence in the tomb of several images of the deceased that could be used as replacement bodies in case the mummy was damaged demonstrates the importance of preserving the body. Although much of the funerary artifacts recovered through excavation have been negatively affected by theft and damage to the tomb.

|

| Memphis - Égypte - 500 avant JC. - Groupe de figurines funéraires shabtis au nom de Neferibreheb, daté d'environ 500 avant J.-C. Photo prise par Serge Ottaviani le 24 avril 2013 |

How do archaeological and textual evidence complement each other in understanding burial practices?

Although archaeological and artistic evidence from Egyptian tombs provides some information about burial practices, knowledge remains incomplete without reference to texts, including inscriptions that accompany scenes of cultic activity, funerary literature, and biographical inscriptions in tombs. These texts provide the rationale for the construction of tombs. In simpler terms, before the New Kingdom, tombs were modeled after the homes of the living, while after the New Kingdom, tombs were constructed to reflect aspects of the afterlife. The texts are particularly useful in outlining the steps involved in funerary worship, defined here as ritual activities centered around the cemetery and the deceased.

What is the mouth-opening ritual in ancient Egyptian burials?

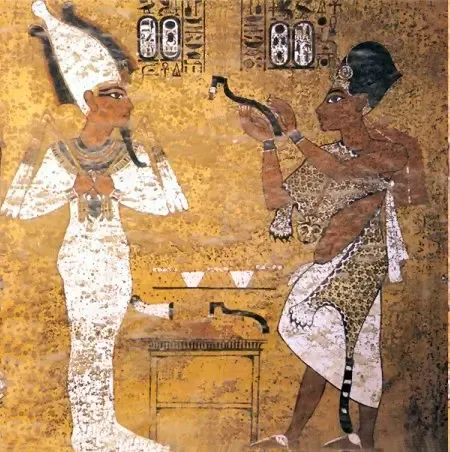

The mouth-opening ritual was a burial ritual that accompanied the placement of funerary objects in the tomb - a necessary step in the rebirth of the deceased. A few New Kingdom tombs (such as the Thebes tomb of the 18th Dynasty minister of Thutmose III, Rakhmir) have provided detailed texts and images of the rituals that constituted this ceremony, most elements of which likely took place in the tomb. These rituals were served by statues, scarabs, sacred animals, temples and, most importantly, the mummy. New Kingdom scenes show statues that were dressed in various materials, cleansed with water and offered as animal sacrifices. Priests would touch the mouth of the ritualized body with a number of items to “open” it. Spells were recited to accompany these rituals to make them effective.

|

| Ay performing the Opening of the Mouth ceremony at Tutankhamun: Wall painting from Tutankhamun's tomb (KV 62), dated circa 1323 BC. Created by an ancient Egyptian artist. Source: aegyptenprojekte.de. |

What role did daily offerings play in ancient Egyptian funerary practices?

Most aspects of funerary rituals were designed to last forever, as the spirit of the deceased required daily offerings of food, incense, and drink in order to survive. The eldest son of the deceased was responsible for making the daily offerings and is often depicted on tomb walls doing so; by performing the ritual, the eldest son fulfilled the mythical role of Osiris's son, Horus. However, a priest hired by the family usually performed the ritual activity on behalf of the eldest son, and the priest's pay included the use of the offerings after the deceased's spirit had taken.

How did festivals of the dead reflect ancestor worship in ancient Egypt?

Ritual activities such as festivals of the dead provide evidence of ancestor worship among the ancient Egyptians, although they usually only extended for one or two generations. Festivals of the dead were held on the new year, among other days, and involved celebrating in the courtyard of the tomb with music, dance, and food. Some other evidence of ancestor worship includes letters written to the dead, which suggest that the spirit of the deceased could help - or harm - the living, and what were later called ancestor statues found in the houses of the city monastery. There appears to have been no formal rituals in funerary worship centered around ancestor worship.

What insights do the Pyramid Texts provide about ancient Egyptian afterlife beliefs?

Egyptian funerary literature provides information about the afterlife as defined by society and helps shed light on many aspects of the burial process and funerary worship.

How did funerary literature evolve from the Old Kingdom to the Middle Kingdom?

The Pyramid Texts, so named because they were first found in an Old Kingdom royal tomb, are the earliest examples of Egyptian funerary texts. Although the earliest pyramid texts were discovered in the pyramid of Onas, the last king of the Fifth Dynasty, and some were also found in the tombs of queens in the late Sixth Dynasty, their language and imagery seem to reflect older traditions, perhaps first preserved orally. The restriction of pyramid texts to royal tombs emphasizes the differences between royal and non-royal burials during the Old Kingdom - already seen in the massive size of the royal pyramid tomb versus the relatively small non-royal mastaba - and the pyramid texts describe in part the ascension of the dead king into heaven as a god to join the other gods. Biographical inscriptions show that non-royal individuals did not reach the afterlife during the Old Kingdom but continued to “live” in their tombs; they did not become gods, but their “ka” lived near the divine dead king. This religious belief was also physically represented by the rows of mastaba tombs of officials built near and around the royal pyramids. But before the Middle Kingdom, non-royal individuals had access to some texts on the afterlife. Some pyramid and sarcophagus texts began to appear in private tombs. By the Eleventh Dynasty, and then later in the Middle Kingdom, copies of pyramid texts appeared frequently on the walls of the tombs of non-royal officials and on the walls of their sarcophagi. In addition, sarcophagus texts - a special later version of funerary literature partly derived and edited from pyramid texts - also appeared regularly. These new texts contained the knowledge that the deceased needed to attain the afterlife, wishing to be in the company of the underworld god Osiris and to travel in the bark of the solar god Ra. The underworld of Osiris, now synonymous with the heavenly afterworld previously seen in the pyramid texts, was inhabited by demons and other dangers that the deceased must recognize and be able to circumvent with the knowledge contained in this body of information.

What is the significance of the Book of the Dead in New Kingdom burials?

In the New Kingdom, another development in funerary literature took place. This collection of spells, called the Book of Day-Going (the Book of the Dead), comprises about two hundred spells. Some individual spells or groups of spells are inscribed on grave goods, jewelry, amulets, and architectural elements - but the largest group is found on papyrus scrolls. In the Book of the Dead, the deceased continued to wish to see the gods Osiris and Ra in the afterlife (although during the Amarna period, when the ruler Akhenaten only worshipped the solar disk called Aten, the spells in the Book of the Dead did not refer to the underworld of Osiris, but included wishes that the deceased would receive offerings in the tomb and see Aten). The afterlife that the deceased hoped for was in many ways identical to the world of the living. The other world was thought to contain a river, like the Nile; there were fields on both sides of the river, where food was produced; and the sun traveled across the sky of the underworld at night after setting in the west, just as it traveled from east to west across the sky of the physical world during the day. This daily “death” of the sun led to the placement of most tombs on the west bank of the Nile, as well as the placement of some tombs with their heads or faces facing west.

How was the judgment of the dead described in the Book of the Dead?

To reach the underworld, the dead had to be judged to be free from sin. The Book of the Dead spell book described the judgment of the dead that allowed each of them to become Osiris. The vignette accompanying that talisman showed the deceased dressed in white robes entering before the god Osiris and the forty-two gods who served as judges. Believed to be the seat of one's personality, his or her heart appeared on one side of the scales and the feather of Maat, the goddess of justice, on the other. A crocodile-headed creature waited nearby to eat the heart if it was judged unworthy, thus condemning the unfortunate deceased to a second, permanent death. If the deceased was judged worthy, he or she was allowed to enter the presence of Osiris forever.