The Invention of Cuneiform Writing and the Birth of Sumerian Schools

The Sumerian schools were the direct corollary of the invention and development of the cuneiform writing system, Sumer's most important contribution to civilization. The first written documents were found in a Sumerian city called Uruk. These documents consist of more than a thousand small clay tablets containing primarily fragments of economic and administrative memoirs written on them. But among them are several tablets containing word lists designed for study and training. This means that as early as 3000 BC, some scribes were already thinking about education and learning. Progress was slow in the following centuries. But by the middle of the third millennium, there must have been a number of schools throughout Sumer where writing was taught systematically. |

| School Life in Sumerian Civilization |

The Role of Sumerian Schools in Administrative and Economic Development

In the ancient city of Shurupak, the birthplace of the Sumerian “Noah,” a large number of “textbooks” dating back to around 2500 BC have been discovered. However, the Sumerian school system did not mature and spread until the latter half of the third millennium. The vast majority of these books were administrative in nature, covering every stage of Sumerian economic life. We learn from them that the number of scribes who practiced their profession during those years was in the thousands. There were junior and “senior” scribes, royal and temple scribes, scribes who specialized in certain categories of administrative activities, and scribes who became senior government officials. All these reasons lead us to assume that many scribal schools of great size and importance flourished throughout the country. |

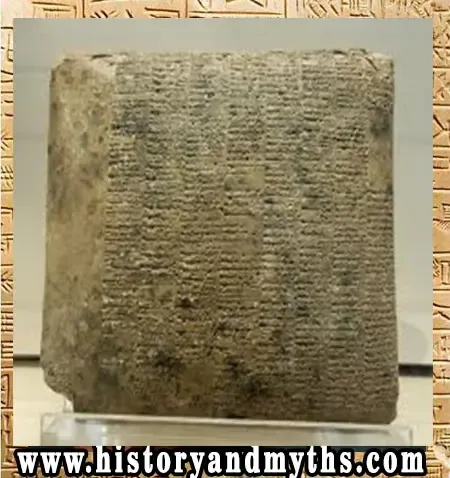

| Shuruppak-tablet |

Daily Life of Students in Sumerian Schools

Hundreds of practice boards have been discovered, filled with all sorts of exercises prepared by the students themselves as part of their daily homework. The texts discovered range from the scribbled scratches of a first grader to the neatly written marks of an advanced student about to become a “graduate.” These ancient “notebooks” tell us a lot about the way the Sumerian school taught and the nature of its curriculum. These ancient “notebooks” tell us a lot about the Sumerian school's teaching method and the nature of its curriculum. Ancient Sumerian teachers themselves liked to write about school life, and many of their writings on the subject have been found, at least in part. From all these sources we get a picture of the Sumerian school - its aims and objectives, its students and teaching staff, its curricula and teaching methods. This is unique for an early period of human history.The Sumerian School Curriculum and its Cultural Significance

The primary purpose of the Sumerian school was to train the scribes required to fulfill the economic and administrative requirements of the land, especially those of the temple and palace. This remained the main objective of the Sumerian school throughout its existence. However, in the course of its growth and development, and especially as a result of its ever-expanding curriculum, the school became the center of culture and learning in Sumer. Within its walls flourished the learned scholar, the man who studied all the theological, botanical, zoological, mineralogical, geographical, mathematical, grammatical, and linguistic knowledge of his time. |

| balance-sheet-tablet |

Creative and Literary Education in Sumerian Schools

Moreover, unlike today's educational institutions, the Sumerian school was also a center for what could be called creative writing. The literary creations of the past were studied and copied, and new books were also composed here. While most Sumerian school graduates became clerks in the service of the temple and palace, there were also those among the country's rich and powerful who devoted their lives to teaching and learning.Like university professors today, many of these ancient scholars relied on teaching salaries to make a living, and in their spare time they spent their time researching and writing.

Sumerian Schools: Centers of Knowledge and Culture

The Sumerian school, which may have begun as an annex to the temple, over time became a secular institution, and its curriculum also became largely secular in nature. Teachers were paid, apparently, from tuition fees collected from students.Education was neither public nor compulsory. Most students belonged to wealthy families; the poor could barely afford the cost and time required for prolonged education. There is not a single woman listed as a scribe in these documents, so it is likely that the student body of the Sumerian school was composed of males only.

Teachers and Students: Relationships and Methods in Sumerian Schools

The head of the Sumerian school was the “expert” or “teacher” and was also called the “father of the school” while the pupil was called the “son of the school”. The assistant teacher was known as the “elder brother”. Some of his duties included writing new tablets for the pupils to copy, reviewing the copies made by the pupils, and listening to them recite their lessons from memory. Other faculty members included the “man in charge of painting” and the “man in charge of Sumerian”. There were also observers responsible for attendance and the “man with the whip,” who was most likely responsible for discipline. We know nothing about the rank of the school's staff, except that the headmaster was the “father of the school”. We know nothing about their sources of income. Perhaps they were paid by the “school father” from the tuition fees he received.Disciplinary Methods and Their Impact on Sumerian Education

Regarding the Sumerian school approach, we have an abundance of data from the schools themselves, which is actually a unique case in early human history. In this case, we do not need to rely on statements made by the ancients or infer from scattered fragments of information. Rather, we have the written productions created by the schoolchildren themselves, from the first attempts of beginners to the copies of advanced students whose work is so well prepared that it is difficult to distinguish it from the work of the teacher himself. From these school products we realize that the Sumerian school curriculum consisted of two main groups: The first can be characterized as semi-scientific and academic, and the second as literary and creative.When examining the first, or semi-scientific, group, it is important to emphasize that the topics did not emerge from what we might call a scholarly motivation. These books were not originally textbooks, but arose and evolved from the school's main purpose, which was to teach the scribe how to write Sumerian. To fulfill this pedagogical need, Sumerian writing teachers devised an educational system based primarily on linguistic categorization - that is, they classified the Sumerian language into groups of related words and phrases and had students memorize and copy them so that they could easily rewrite them. In the third millennium BCE, these “textbooks” became increasingly more complete, and gradually grew until they were standardized for all Sumerian schools. Among them we find long lists of the names of trees and reeds; all kinds of animals, including insects and birds; towns, cities and villages; stones and minerals. These compilations reveal a considerable knowledge of what might be called the botanical, zoological, geographical and mineralogical heritage.

|

| Schooling-Grammatical-Text-of-Nippur |

Sumerian school students also created various mathematical tables

and many detailed mathematical problems with their solutions.

|

| Schooling-mathematical-text-with-geometric-design |

In the field of linguistics, the study of Sumerian grammar was well represented among the school tablets. A number of them are inscribed with long lists of thematic complexes and verbal formulas, demonstrating a highly developed grammatical approach.

Moreover, as a result of the gradual invasion of the Sumeriansby the Semitic Akkadians in the last quarter of the third millennium BCE, the Sumerians prepared the oldest “dictionaries” known to man. The Semitic invaders not only borrowed.

the Sumerian text, but also borrowed Sumerian literary works, which they studied and imitated long after Sumerian had died out as a spoken language. Hence the educational need for “dictionaries” in which Sumerian words and phrases were translated into Akkadian.

The literary and creative aspects of the Sumerian approach were based primarily on the study, copying, and imitation of a great variety of literary compositions that must have originated and developed mainly in the latter half of the third millennium BC. These ancient works, numbering in the hundreds, were almost all poetic in form, ranging in length from less than fifty verses to nearly a thousand. Those that have been found so far are mainly of the following types: Epic myths and stories in the form of narrative poems celebrating the deeds and exploits of Sumerian gods and heroes; hymns to gods and kings.

Little is known so far about the teaching methods and techniques practiced in the Sumerian school in the morning, upon arriving at school, it is clear that the pupil has studied the tablet prepared the day before.

The “big brother” - the assistant teacher - has prepared a new tablet, and the student begins to copies it and studies it.

when it comes to discipline. While teachers encouraged their students, through praise, to do well, they relied primarily on the cane to correct students' mistakes and shortcomings.

A student's life was not simple. He went to school every day from sunrise to sunset. He must have had some vacations during the school year, but we don't have any information about that. He spent many years in his studies and stayed in school from his early youth until the day he became a young man.

|

| Board-with-homework |

Architectural Discoveries of Sumerian Educational Buildings

What was an ancient Sumerian school like? In several excavations in Mesopotamia, buildings have been discovered that for one reason or another have been identified as possible schools - one at Nippur, another at Sippar, and a third at Ur. However, except for the fact that a large number of slabs were found in the rooms, there was nothing to distinguish them from the rooms of ordinary houses. However, while digging in ancient Mari west of Nippur, the French discovered two rooms that certainly seem to have the physical features that would be characteristic of a school room, especially since they contain several rows of benches made of burnt bricks with seating for one, two, or four people. |

| Sumerian-school |

Sumerian Students' Perception of Their Educational System

How did the students themselves feel about this educational system? For at least a partial answer, we turn to a true Sumerian account of school life that took place and was written nearly four thousand years ago but was collected and translated in modern times. It is particularly instructive regarding the relationship between pupil and teacher, and offers the unique “first” experience in the history of educationOne of the most interesting human documents excavated in the Near East is a Sumerian essay on the daily activities of a pupil. Written by an unknown teacher who lived around 2000 BC, its simple and direct words reveal how little human nature has changed over the millennia. In this ancient essay, a Sumerian schoolboy is afraid to be late for school “for fear that his teacher will beat him with a stick.” When he wakes up, he urges his mother to hurry up and make him lunch. At school, whenever he misbehaves, his teacher and assistants cane him. As for the teacher, his salary seems to have been meager at the time

This article, no doubt authored by one of the “masters” at the House of Tablets, begins with a direct question to the disciple: “Disciple, where have you been since the early days?” The disciple answers,” I went to school.” The author then asks, “What did you do at school?” Then comes the pupil's answer, which takes up more than half of the document, saying in part, “I read my painting, ate my lunch, prepared my (new) painting, wrote it, finished it, then they gave me my oral work, and in the afternoon, they gave me my written work. When school was over, I went home, entered the house, and found my father sitting there. I told my father about my written work. Then I read my board to him, and my father was pleased.

When I woke up early in the morning, I faced my mom and said, “Give me my lunch, I want to go to school.” My mom gave me two rolls and I went; my mom gave me two rolls and I went to school. At school, the supervisor said to me: “Why are you late?” Frightened and with my heart pounding, I walked in front of my teacher and bowed respectfully

But whether he bowed or not, it seems to have been a bad day for this student. He had to receive beatings from various faculty members at the school for inappropriate behaviors such as talking, standing up, and walking out of the gate. Worst of all, the teacher told him, “Your hand (dirty) is unsatisfactory,” and hit him with the cane. Apparently, this was too much for the boy, so he suggested to his father to invite the teacher home to calm him down with some gifts. The composition continues: “His father listened to what the student said. The teacher was brought from the school, and after entering the house, he sat in the seat of honor. The disciple took care of him and served him, and all that he had learned of the art of writing on tablets he revealed to his father.”

The father then invited the teacher, drank wine and dined, “dressed him in a new robe, gave him a gift, and put a ring on his hand.” Motivated by this generosity, the teacher reassured the aspiring writer with poetic words that read in part, “Young man, because you have not neglected my word, nor forsaken it, I wish you to reach the pinnacle of the art of writing, I wish you to reach it fully. “Let your brothers be their leader, let your friends be their leader, and let your rank be higher than that of the schoolboys. You have done well in school ... and you have become a learned man.

Related Articles